In his book Scenes from a Revolution (2009), Mark Harris identifies Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, both nominees for the 1967 Best Picture Oscar, as the vanguard of what would come to be known as New Hollywood. The Graduate’s status as a totem of the New Hollywood generation is curious. It is unmistakeably New Hollywood in style—the Simon & Garfunkel pop soundtrack; method actor Dustin Hoffman at the centre; a liberal, matter-of-fact depiction of sex—but was able to distance itself from its cultural moment rather than simply ride the wave.

Whereas the filmmakers of New Hollywood were lionised for being headstrong and radical, The Graduate urges caution. Bonnie and Clyde was highly controversial – looking to definitively separate itself from the morals of the previous generation; The Graduate sympathises with the previous generation, and is highly critical of the rashness and self-centred nature of its young characters. While the youth of the 1960s pictured themselves as the centre of a cultural revolution, The Graduate suggested this sense of revolution was something that recurred every generation, often proving self-defeating.

Remarkably for a film released nearly fifty years ago, The Graduate’s structure aligns perfectly with that of modern romantic-comedy.[1] The film uses many common rom-com tropes as devices to aid its satire, at points satirising romantic-comedy itself.

When crudely described, the narrative of The Graduate amounts to: Benjamin, a young man looking for direction, meets Elaine, a young woman who seems to be a perfect match. Despite a disastrous first date, they fall in love. They argue, they reconcile. Her parents, his wrathful ex, her perfect fiancé stand in the way, but the two of them succeed against the odds, as he makes a grand romantic gesture at her wedding. It is only when the details of this become filled in, that The Graduate starts to look less conventional than this cursory retelling would have you believe. If we take some of these tropes and look at the context of the way they are employed in The Graduate, a very different, more subversive story emerges.

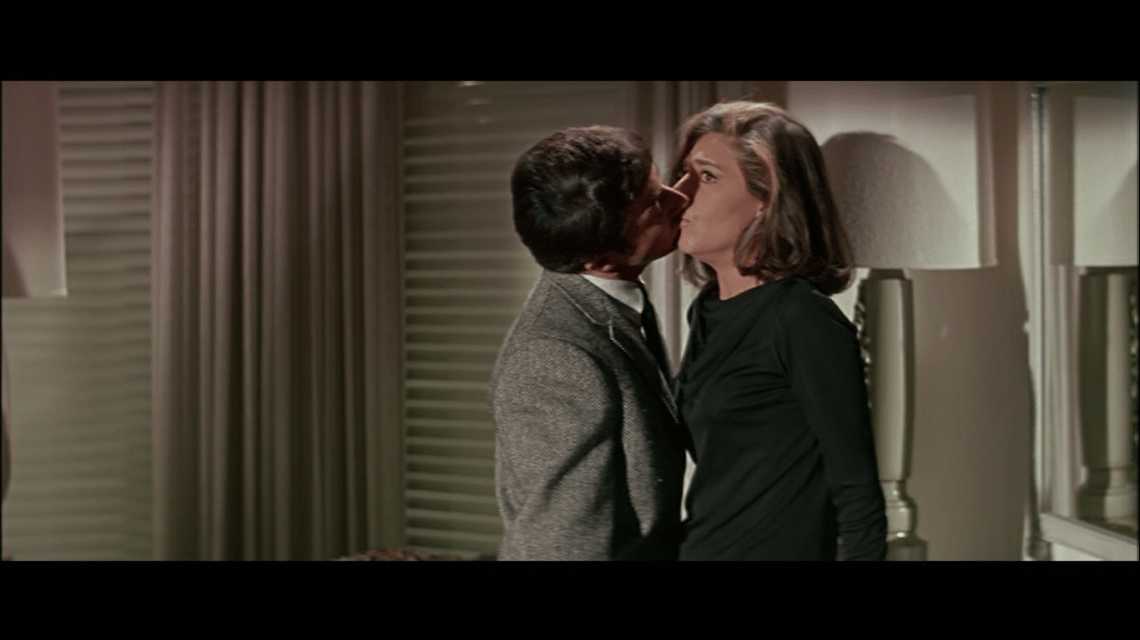

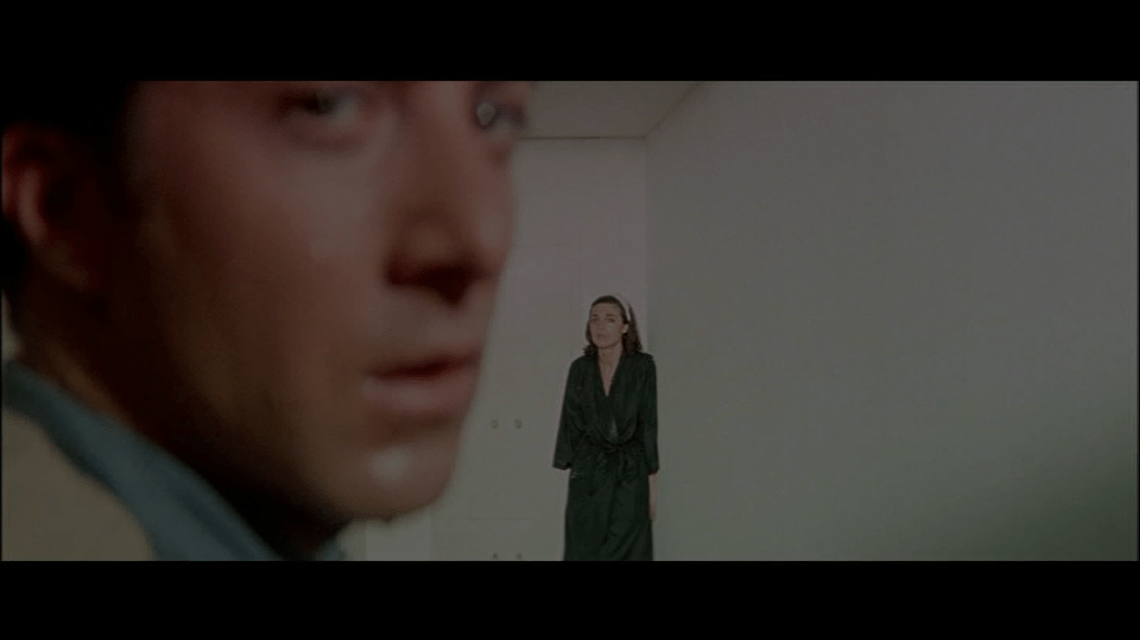

Firstly, and most famously, the ex-lover posing a problem in The Graduate is Mrs Robinson, the love interest’s mother. Not only does Mrs Robinson provide an unusually Oedipal kink in the rom-com narrative, she also provides the film with its pathos. The failing marriage of the Robinsons shadows the main romantic storyline of protagonist Ben and Mrs Robinson’s daughter, Elaine, suggesting an uncomfortable look at where their relationship is headed. At a pivotal scene midway through the film, Mrs Robinson tells Ben about how she found herself trapped in a loveless marriage. Rather than listen, or even offer sympathy, Ben laughs at the pathetic origins of Mrs Robinson’s marriage. At the end of the film, his sober look on the back of the bus suggests that he too may have trapped himself in a similar union.

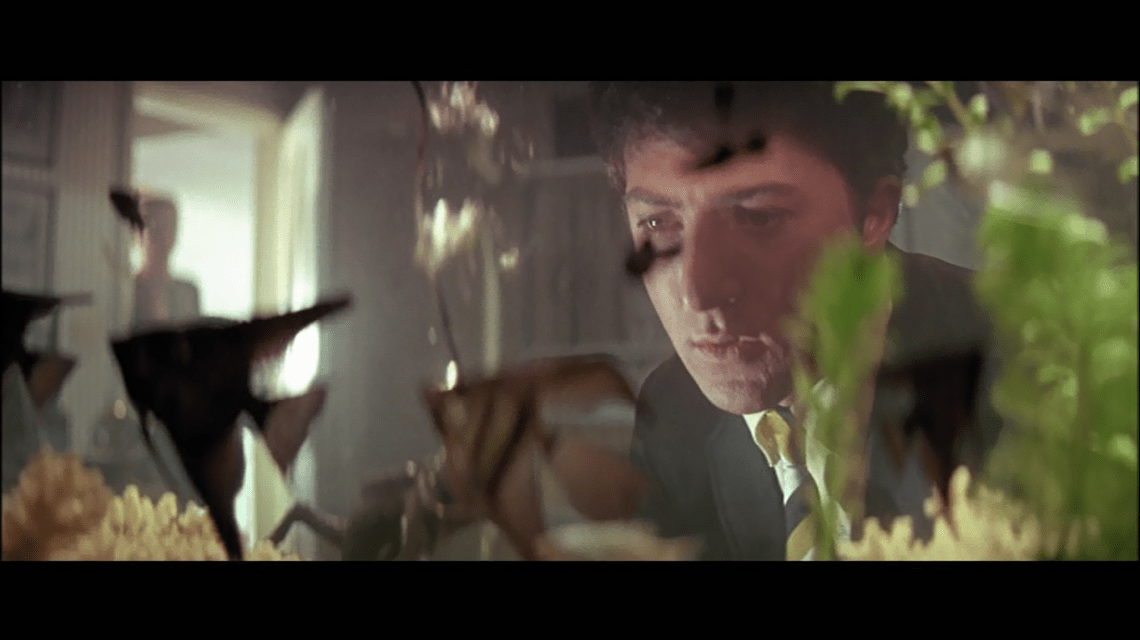

This scene of Mrs Robinson’s confession marks a shift in the film’s sympathy. Benjamin becomes more selfish and obsessed, while Mrs Robinson becomes a tragic antagonist. Benjamin almost forces himself into a romantic storyline as a means of providing his life with some impetus. The opening credits have Ben stood on a walkway, letting it carry him to his destination as people walk past him in both directions.

At first Ben seeks this romantic storyline with Mrs Robinson, but finds his offers to buy her a drink or to talk shut down—“I don’t think we have much to say to each other”—as she prefers to dispense with any illusions of romance between them.

On his first date with Elaine, he finds a woman more receptive to his ideas of romance. While he found the idea of their union unappealing when it was being heavily pushed by his parents and her father, he all of a sudden finds her attractive once Mrs Robinson forbids him from taking her out. In classic romantic-comedy convention, a relationship is only desirable when there is strong opposition towards it. As the opposition mounts up throughout the film, he becomes single-mindedly devoted to the idea of being with Elaine. He follows her up to Berkeley and announces to his parents his intention to marry her, despite the fact that “to be perfectly honest, she doesn’t like me”. Although lauded as a “track star” throughout the film, the only time he gains any motion is when chasing Elaine.

It is as though he is being guided by an internal romantic-comedy structure. Only the understanding of cinematic convention, that the lead gets the girl, makes the audience feel as though the two should be together. His affair with her mother suggests that theirs is not a romance for the ages, and his later actions are also less than considerate – he is rude and cruel on their first date, and later shows no concern for the family trauma he’s reminding her of by following her up to Berkeley. It’s more that she’s the only person of his own age he interacts with – his welcome home party is attended only by people his parent’s age and older. As soon as she’s forgiven him, he immediately talks of marriage. He goes from having no direction to the opposite extreme, wanting to rush into everything. He never considers the lives of those—such as Mrs Robinson—that he is ruining in his pursuit of what he wants.

This is not too distant from many romantic-comedy protagonists, only in this case, director Mike Nichols and screenwriters Buck Henry and Calder Willingham give us small insights into the surrounding carnage Ben leaves, that places his more conventionally ‘romantic’ actions in a different, unlikeable light.

The film’s final ten minutes combine so many rom-com tropes it feels like outright parody – despite being made decades before most of the films to utilise those elements. Simon and Garfunkel playing on the soundtrack, Benjamin races to stop the wedding between Elaine and Carl Smith. As his car breaks down, he finds himself having to run. The church itself looks very sterile and oddly fake, and the organ is comically out of tune, puncturing the usual grandeur and romance of cinematic weddings.

That Benjamin arrives just as Elaine kisses the groom, confirming the marriage, would seem to be an insurmountable obstacle, but Ben rushes past it with no consideration, as he has for all other obstacles throughout the film. He fights off the wedding guests by swinging a four foot crucifix, and escapes with Elaine onto a bus.

Although ridiculous, if the film ended here, it could still fairly be termed a rom-com. But the camera holds, and it provides The Graduate with its defining moments. Ben and Elaine alternate glances at each other, but never catch the other’s eye – betraying a couple out of sync. Their laughs fade, as their faces take on an expression of more sober reflection. Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence” returns on the soundtrack – a song that has been associated with Ben’s ennui throughout the film. Now that the romantic comedy structure has played itself out, the characters find themselves committed to one another, and they are no longer sure what to do, or how strong their feelings for one another really are now that the rebellion has been won.

In a further irony, their rebellion has just achieved what their parents wanted from the start – Ben and Elaine together. As the bus drives away, we are reminded of the words of Mrs Robinson, and realise that Ben and Elaine have, in trying to gain independence from their parents, simply repeated their mistakes.

[1] Even more remarkable when considering that the first true cinematic romantic comedy, It Happened One Night (1934), was released only eighty years ago, and When Harry Met Sally (1989), the film most modern romantic comedy uses as a template, was released over twenty years after The Graduate.

*

Dan Norman is a recent graduate of English Literature at The University of Manchester, UK.

The Graduate is the most consistently funny coming-of-age romantic movie I’ve ever seen. Unlike other films in which teen boys hook up (or joke about hooking up) with one another’s mothers, in The Graduate the tearing of the family fabric actually has impact. You can see the emotional damage being wrought on all the Robinsons as individuals. This pain also brings about the most hilarious scene, in which Mr Robinson confronts Ben in his boarding house with the accusation that he is “scum”, “filth”, and “a degenerate” and is attempting to sully both his wife and daughter as some kind of personal vendetta. His egocentric belief that it’s all about him is really the icing on the cake for me. And all the satire throughout The Graduate is heightened on repeat viewings in the knowledge that Benjamin, despite his resistances, will wind up the same way as his parents.

Sorry, my comment is a little half-baked…

no its not, it’s fully baked