“We must make persistent efforts, press ahead with indomitable will, continue to push forward… to achieve the Chinese dream of great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”[1]

President Xi Jinping, 12th National People’s Congress, Beijing, March 17th, 2013.

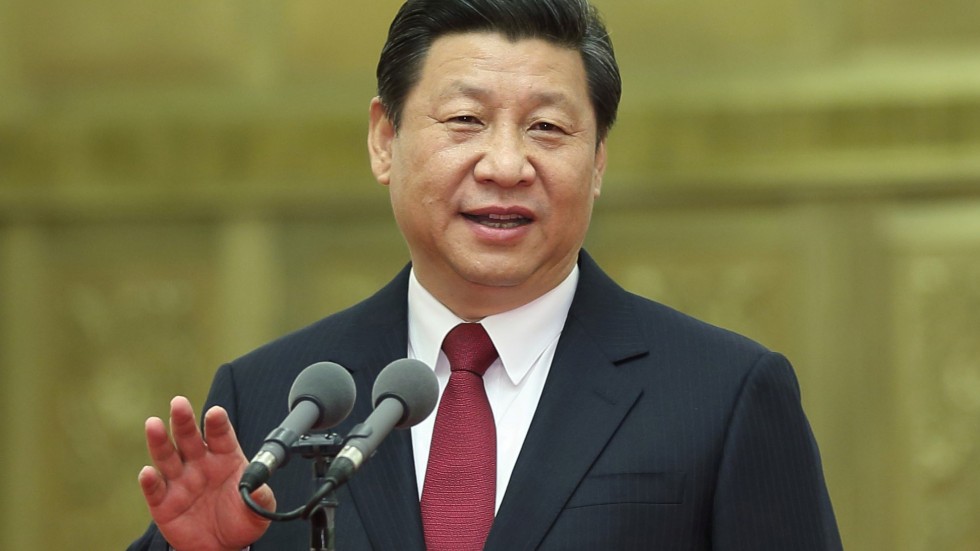

As President Xi’s (pictured, below) speech to the National People’s Congress in Beijing back in 2013 exemplifies, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) today explicitly promotes Chinese nationalism as being the fundamental basis for achieving the ‘Chinese Dream’: to make China the world’s most powerful nation. Western scholars such as Mary Wright have reflected this outlook, arguing that nationalism was the “moving force” that inspired “action and change” during the multiple Chinese revolutions in the first half of the twentieth century. This essay will revise that historiographical interpretation, analysing how nationalism served to ‘break’ China between 1901-37, before the CCP used nationalism as the ideological foundation to ‘make’ China from 1937 to 1949.[2]

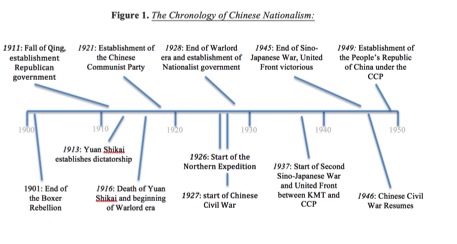

Throughout the second half of the 19th century, the ruling Qing dynasty suffered endless international humiliations at the hands of the British, French and German empires. Extensive droughts and a lack of political and social reform further fostered nationwide civil disorder, resulting in China’s last imperial dynasty being overthrown by a Republican revolution in 1911. Accordingly, the groups that dominated Chinese politics from 1911, until the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 by the CCP, all presented Chinese nationalism as an ideological foundation for creating a modernized and united Chinese state, strong enough to resist the interests of foreign imperial powers. Thus, despite the incredible complexity of Chinese politics during this period, (illustrated, below) whether nationalism served to ‘make’ or ‘break’ China was fundamentally determined by the extent to which Chinese political groups use the pursuit of these nationalist goals to serve their own interests.

It is not a matter of arguing for or against Chinese nationalist ideology; rather we need to understand how that nationalism both consolidated and threatened to undo the stability of the country, depending on the circumstances of its deployments. First, I want to consider how Chinese warlords manipulated nationalism to pursue their own political purposes, effectively ‘breaking’ China during the warlord era, (1916-28). Secondly, I will analyze how China’s intellectuals and bourgeoisie ‘broke’ China, as the nationalism they endorsed in the 1911 Revolution and May 4th and May 30th movements served the ideals and interests of their proponents. Finally, I shall evaluate the contrasting conceptions of nationalism forwarded by the Kuomintang, which continued to ‘break’ China, and the mass nationalism forwarded by Chinese Communists, which served to ‘make’ China by uniting the Chinese peasantry in support of a united Chinese government, strong enough to resist the interest of foreign powers.

Warlord Nationalism

From 1916-28, powerful individual military commanders, who became known as Chinese ‘warlords’, used nationalism to further their own political and military agendas. Following the death of warlord Yuan Shikai, who established a military dictatorship over China following the Republican Revolution of 1911, Republican politics became militarized as “different political forces turned to the military to resolve seemingly irreconcilable political conflicts”.[3]

Yuan Shikai, 1911

Zhang Xun, who called a conference of thirteen northern Chinese warlords at Xuzhou immediately after Yuan Shikai’s (pictured, above) death, set the precedent for warlords to use nationalism to serve their own political interests. Such Chinese warlords were purely interested in securing their “military interests”, but were aware their conference could clearly be criticized for promoting political militarism.[4] Accordingly, the conference’s speakers couched their proposals – to use military force to remove Republican politicians who threatened warlord influence – in a nationalist framework:

“if we military men are restrained by established precedent… then we might as well stand and wait for the demise of the nation.”[5]

As McCord expertly summarizes, this provides a “classic example” of “nationalist justification”for the military intervention of warlords in civilian politics. Moreover, the actions of Duan Qirui, the warlord Premier of the Republic from 1916, epitomized how warlords used nationalism as a political tool.[6] In response to the Xuzhou conference, he ordered that his fellow warlords should not “exceed their authority” by using military force to intervene in the “administration of the nation”.[7] However, when the National Assembly refused to support his demands for Chinese intervention in the First World War a year later, Duan surrounded the assembly with a military mob, threatening Republican politicians until they “agreed to the declaration of war against Germany that he desired.”[8] The actions of Xun and Duan exemplify how the use of nationalism by warlords to legitimize military conflict only served to ‘break’ China in political terms, because their actions “weakened national unity” and the ability of the Chinese government to “resist the pressures of foreign powers”.[9]

The division of China amongst major Warlords, circa 1925

Another manipulation of nationalism, this time by Kwangsi warlords, also deeply unsettled Chinese social, political and economic life. The Kwangsi warlord clique claimed “to serve nationalism by developing their own region”: consequently, warlords permitted the nationalist agitation that swept through their region from January 1926.[10] This agitation, however, rapidly developed into public demonstrations for the end of official corruption, the opium trade and for higher wages in the Kwangsi region. In response, from April 1926 the warlords viciously prevented further nationalist activity as they has no intention of implementing “major social reforms”, which could threaten their political authority.[11]

The Kwangsi clique’s manipulation of nationalism was reflected throughout China, as warlords ignored local administration, education and public works, whilst public funds were frequently mishandled or embezzled to fund self-serving military campaigns.[12] Both the warlord conference in the north and the campaigns of the Kwangsi clique demonstrate the strategy amongst warlords of paying lip service to nationalism in order to legitimize their regimes, before ensuring that the social or economic reforms contained within the ideals of nationalism itself never actually saw the light of day.

Intellectual and Bourgeoisie Nationalism, 1911-1927

But such military-oriented politics was not the only kind of self-serving ‘nationalism’ to surface in China in the course of the twentieth century. The peculiar brand of national ideology fomented by intellectual and bourgeois groups during the Xinhai Revolution (1911), the May 4th Movement (1919) and the May 30th movement (1925), was just as damaging to the social, political and economic life of China as the more cut-and-thrust manipulation of ideology propagated by the Kwangsi and other warlord groups at the turn of the century.

As foreign powers continued to humiliate China following the Boxer Rebellion, Liang Qichao’s conclusion that “Only the nation is our father and mother” exemplified the belief amongst China’s most prominent intellectuals that nationalism could be a productive force that could ‘make’ China, by stimulating modernization, unity and resistance to foreign powers.[13] Intellectual nationalism further spread among students during this period, with numerous intellectual newspapers such as The Revolutionary Army agreeing that the white man’s “complete mastery over China” could only be checked by “the awakening of Chinese nationalism”.[14] Although unlike the warlords, these groups genuinely supported nationalist ideology, students and intellectuals also believed only they were capable of successfully achieving a nationalist revolution. Consequently, this limited, elitist-intellectual nationalism failed to ignite the national consciousness of the Chinese people, which could have provided the basis for creating a strong, modernizing and unified Chinese government. Ultimately, this meant the Republic was easily overthrown by Yuan Shikai, whose dictatorship set the precedent for the militarization of Chinese politics during the warlord era.

The May 4th and May 30th movements further illustrate how the limited nationalism of intellectuals and the Chinese bourgeoisie continued to ‘break’ China following the 1911 revolution. In response to Germany’s possessions in Shandong being transferred to Japan following the First World War, Peking students organized large-scale nationalist demonstrations. Their manifesto, which stated, “we students have been educated and self-cultivated for so long that we will advisedly follow our national traits of wisdom, virtue and courage”[15], illustrates how students continued to believe that only intellectuals could successfully use nationalism to ‘make’ China, with the result that “the peasantry was almost entirely absent from the May Fourth Movement”.[16] Furthermore, the majority of bourgeoisie groups only supported the movement because it enabled them to manipulate nationalist rhetoric to legitimize their prolonged boycott of Japanese industrial goods, which served their own economic interests by reducing industrial competition.[17]

A similar pattern was reflected during the May 30th Movement of 1925: the bourgeoisie initially supported the “patriotic and anti-imperialist fervor” of students protesting the murder of Chinese demonstrators by British policemen, before condemning the movement “when faced with the risk of sympathy strikes being staged in their own factories”.[18] In both the May 4th and May 30th movements, we can see how China’s intellectuals and bourgeoisie, just like the more militarily-minded provincial warlords, forwarded a limited concept of nationalism which fundamentally served their own political ideals and economic interests. Neither warlords nor intellectual-bourgeoisie could foster the kind of mass nationalist spirit amongst the Chinese people which was essential to create a unified and modernized Chinese state that could resist foreign intervention.

Kuomintang and Communist Nationalism, 1927-1945:

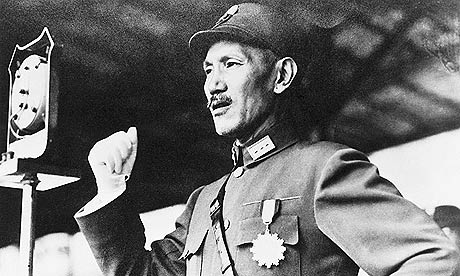

The KMT, or Chinese Nationalist Party, was founded by Chinese Revolutionary Sun Yat-Sen shortly after the 1911 Revolution, but only controlled a relatively small part of southern China throughout the warlord period. From 1926, however, the KMT was led by powerful warlord Chiang Kai-shek (pictured, below) who, in alliance with the smaller Chinese Communist Party, created the National Revolutionary Army which proceeded to defeat China’s most powerful warlords and unite the country.

Chiang Kai-Shek

As the KMT and CCP were defeating warlord governments and unifying China in 1927, their contrasting conceptions of nationalism came to the fore. The right wing of the KMT pursued a limited revolutionary nationalism which “almost entirely” served the ideals and interests of China’s intellectuals and bourgeoisie; by contrast, the Communist Party wanted to instigate a mass nationalist movement amongst the Chinese peasantry.[19]

Consequently, as CCP revolutionaries mobilised the masses “in patriotic rallies and parades” to spread nationalism throughout China, local KMT military commanders arrested and murdered local communists to ensure their concept of limited nationalism dominated China from 1928.[20] Nevertheless, both intellectuals and China’s bourgeoisie continued to support KMT nationalism as it enabled them to retain their “privileged status” in Chinese society.[21] Therefore, as Johnson has pointed out, the limited nationalism of the KMT, in maintaining the interests of China’s intellectuals and the bourgeoisie, ended up becoming “a nationalist movement with a head and no body”, preventing the creation of a mass nationalist movement which was essential to unify and modernise the nation as a whole.[22]

Despite the purge of communists from the KMT in 1927, a decade later the CCP and KMT once more formed a ‘United Front’ against a common enemy, Japan. Although prior to the Sino-Japanese war, the Chinese peasantry remained “indifferent to ‘Chinese’ Politics”, from 1937 the CCP recognized that Japanese aggression could provide a catalyst for creating the mass nationalism needed to ‘make’

China.[23]

Throughout the Sino-Japanese war the CCP ensured “nationalism was given a specific, external definition – it meant resistance to Japan”, as this piece of propaganda demonstrates:[24] “Japan has invaded our Shansi, killed large numbers of our people, burned thousands of our homes, raped our women… Everybody! … “Defend our anti-Japanese patriotic people’s government!”[25]

The repeated emphasis of Japanese violence against ‘our’ land, homes and women illustrates how the CCP framed nationalism within the theme of collective outrage and resistance in order to construct and mobilize the emerging national consciousness of the Chinese peasantry.

Mao Tse-Tung, 1939

Whilst Mao recognised the need for Chinese nationalism to include “full rights for the people”,[26] the KMT diverted from Sun Yat-Sen’s principle of land reform from 1927, supporting instead the rural conservatism of China’s agrarian landlords.[27] Similarly, whilst KMT forces frequently requisitioned and pillaged the Chinese peasantry throughout the Sino-Japanese war, the CCP prioritised the respectful treatment of Chinese peasants.[28] The popular, mass nationalism of the CCP, in making the peasantry its privileged subject, was well placed to foster a national identity as it encouraged the Chinese masses to undertake the “most crucial” task of nationalism: “defending the nation from external aggression”.[29]

Overall, the limited nationalism of the KMT fundamentally served the ideals and interests of China’s intellectuals and bourgeoisie. From 1937, however, it “forfeited the leadership of nationalism”.[30] The mass nationalism stoked by the CCP within the context of the Sino-Japanese war fostered a national consciousness amongst the Chinese people which ultimately laid the ideological foundation for the unification of China under the CCP in 1949. a mindset that continues, despite its permutations, to undergird the belief in Chinese national progress still espoused in the presidential speech at the 2013 National People’s Congress.

Throughout the birth of modern China, every political group used anti-imperialist rhetoric and attempted to construct a unique brand of nationalism in order to legitimise their claims to political power. The nationalisms of military warlords and bourgeoisie intellectuals were both ultimately—fatally—self-serving. Only when Mao’s Chinese Communist Party promoted a mass nationalist ideology during the Sino-Japanese war, which aimed to serve the interests of all Chinese people, did the aim of unifying the nation and repelling foreign powers become truly possible.

*

Joseph Barker is a former History editor of New Critique. He holds a BA in History from the University of Manchester and a double honours MSc/MA in Media and Communication from the London School of Economics and the University of Southern California.

Bibliography:

Liang Qichao, ‘The Concept of the Nation’, in William Theodore de Bary, Sources of Chinese Tradition (Sussex: Columbia University Press, 1999).

Li Yuanhong, ‘Secret Report’, September 1916, in Lai Xinxia, The History of the Northern Warlords (London: Oriental Publishing Center, 2011).

Mao Tse-tung, ‘On new Democracy’, January 1940, Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung: Vol II.

Peking Students, “Manifesto for a General Strike”, May 18th, 1919, in Chow Tse-tsung, The May Fourth Movement (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960).

‘Shansi Sacrifice League leaflet’, September 1938, Japanese War Ministry Archives, vol. 64, no. 3.

Shibao, October 4th, 1916.

‘What does Xi Jinping’s China Dream mean?’, BBC News, 6th June 2013.

Bianco, Lucien, Origins of the Chinese Revolution 1915-1949 (trans., Muriel Bell) (London: Oxford University Press, 1971).

Chesneaux, Jean, Le Barbier, Francois & Bergere, Marie-Clare, China from the 1911 Revolution to Liberation (Sussex: The Harvester Press, 1977).

Cohen, Paul A, Discovering History in China: American Historical Writing on the Recent Chinese Past (Chichester: Colombia University Press, 1984).

Johnson, Chalmers A, Peasant Nationalism and Communist Power: The Emergence of Revolutionary China 1937-1945 (California: Stanford University Press, 1962).

Lary, Diana, Region and Nation: The Kwangsi Clique in Chinese Politics 1925-1937 (London: Cambridge University Press, 1974).

McCord, Edward A, ‘Burn, Kill, Rape and Rob: Military Atrocities, Warlordism and anti-Warlordism in republican China’ in Diana Lary and Stephen Mackinnon, Scars of war: The Impact Of Warfare On Modern China (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2001), pp. 18-50.

McCord, Edward A, ‘Warlords against Warlordism: The Politics of Anti-Militarism in Early Twentieth Century China’, Modern Asian Studies, 30, 4, (1996), pp. 795-827.

Reid, Anthony, Imperial Alchemy: Nationalism and Political Identity in Southeast Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Shiffrin, Harold Z, Sun Yat-Sen: Reluctant Revolutionary (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1980).

Wilbur, Martin C, The Nationalist Revolution in China, 1923-1928 (London: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

Wright, Mary C, ‘Introduction: The Rising Tide of Change’, in Mary C. Wright (ed.), China in Revolution: The First Phase 1900-13, (London: Yale University Press, 1969).

Citations

[1] ‘What does Xi Jinping’s China Dream mean?’, BBC News, 6th June 2013.

[2] Mary C Wright, ‘Introduction: The Rising Tide of Change’, in Mary C. Wright (ed.), China in Revolution: The First Phase 1900-13, (London: Yale University Press, 1969). p3.

[3] Edward A McCord, ‘Warlords against Warlordism: The Politics of Anti-Militarism in Early Twentieth Century China’, Modern Asian Studies, 30, 4, (1996), pp. 795-827, p. 802.

[4] McCord, ‘Warlords’, p. 808.

[5] Li Yuanhong, ‘Secret Report’, September 1916, in Lai Xinxia, The History of the Northern Warlords (London: Oriental Publishing Center, 2011), p. 425.

[6] McCord, ‘Warlords’, p. 808.

[7] Shibao, October 4th, 1916.

[8] McCord, ‘Warlords’, p. 810.

[9] Edward A McCord, ‘Burn, Kill, Rape and Rob: Military Atrocities, Warlordism and anti-Warlordism in republican China’ in Diana Lary and Stephen Mackinnon, Scars of war: The Impact Of Warfare On Modern China (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2001), pp. 18-50, p. 35.

[10] Diana Lary, Region and Nation: The Kwangsi Clique in Chinese Politics 1925-1937 (London: Cambridge University Press, 1974), p. 19.

[11] Lary, Region and Nation, p. 100.

[12] McCord, ‘Burn, Kill, Rape’, p. 35.

[13] Liang Qichao, ‘The Concept of the Nation’, in William Theodore de Bary, Sources of Chinese Tradition (Sussex: Columbia University Press, 1999), p. 298.

[14] Harold Z Shiffrin, Sun Yat-Sen: Reluctant Revolutionary (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1980), p. 94.

[15] Peking Students, “Manifesto for a General Strike”, May 18th, 1919, in Chow Tse-tsung, The May Fourth Movement (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960), p. 139.

[16] Jean Chesneaux, Francois Le Barbier & Marie-Clare Bergere, China from the 1911 Revolution to Liberation (Sussex: The Harvester Press, 1977), p. 73.

[17] Chesneaux, China, p. 73.

[18] Chesneaux, China, p. 160.

[19] Chalmers A Johnson, Peasant Nationalism and Communist Power: The Emergence of Revolutionary China 1937-1945 (California: Stanford University Press, 1962), p. 23.

[20] Martin C Wilbur, The Nationalist Revolution in China, 1923-1928 (London: Cambridge University Press, 1983), p. 100.

[21] Chesneaux, China, p. 195.

[22] Johnson, Peasant Nationalism, p. 24.

[23] Johnson, Peasant Nationalism, p. 5.

[24] Lary, Region and Nation, p. 20.

[25] ‘Shansi Sacrifice League leaflet’, September 1938, Japanese War Ministry Archives, vol. 64, no. 3.

[26] Mao Tse-tung, ‘On new Democracy’, January 1940, Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung: Vol II.

[27] Chesneaux, China, p. 195.

[28] Lucien Bianco, Origins of the Chinese Revolution 1915-1949 (trans., Muriel Bell) (London: Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 155.

[29] Lary, Region and Nation, p. 18.

[30] Lary, Region and Nation, p. 18.